Despite the Memorial Day weekend and the shortened week for U.S. business, the week has been eventful nonetheless. With anticipation mounting for the June 2nd OPEC meeting, the increased potential for a U.S. interest rate hike being signaled by the Fed, and Canadian crude returning to the market, oil markets have been rife with intensity this week.

These market influences have accompanied the Chinese government’s rethinking the value of the yuan in world markets.

On Wednesday May 25, 2016, the Chinese central bank set the value of the yuan at a five year low against the U.S. dollar. The actual move was rather small, amounting to a decline of 0.34%. The exchange rates are set by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) on a daily basis based upon market factors. The implication being that the consistent devaluation stems from underlying uncertainty surrounding the currency.

The continued depreciation of the Chinese currency does little to allay fears of slowing growth and an economy facing turmoil. The decline of Chinese manufacturing has been well documented, and capital has been fleeing the Chinese economy at an alarming rate.

The decline in Chinese growth has far reaching implications for the global economy as well as oil markets.

A Reminder of the Past: A Shift in Perspective

On August 11, 2015, the People’s Bank of China surprised financial markets around the world by devaluing the yuan by 2%, which triggered the biggest one-day drop for the renminbi in more than 20 years. The damage was not limited to just the Chinese currency, as the implications of the devaluation rippled through crude oil and financial markets.

The actions of August 11th would have been enough for most investors… but then the yuan plunged again the following day, falling 3.5% against the U.S. dollar and 4.8% in global markets over the two day period despite PBOC efforts to prop it up.

Many speculated the motivation behind the devaluation was a desire to boost a sluggish Chinese manufacturing sector, which has been a drag on GDP growth results, but others conveyed a broader rationale, and interpreted the policy move as the start of an economic transition.

Under President Xi Jinping, China has announced its desire to pivot its economy from one dependent on manufacturing and exports to one that is driven increasingly by consumer spending and domestic demand. This directive has come hand-in-hand with an effort to open up the country’s financial system to better secure its place in the global economy and to use the outlet to help prevent economic imbalances that occur as a side effect of a closed system.

The intent was to initiate a new phase of currency trading with the Chinese yuan by allowing the currency to “float freely” in an open market dictated by demand and supply of the currency. Allowing the yuan to float would instigate increased use of the currency, which led to the IMF adding the renminbi to the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket of currencies in November 2015. The move came after the IMF evaluated the Asian nation’s standing as an exporter and the yuan’s role as a “freely usable” currency. In a statement, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde noted the yuan’s inclusion is a “clear representation of the reforms” taking place in China.

What Makes a Currency Valuable?

In a world of market-based currencies where bank notes from the world’s central banks freely float against each other, it is important to remind ourselves what makes a currency valuable. A fiat currency, one that is not tied to gold or some other precious metal, is only valuable if there is demand for it. In other words, the dollar is only valuable because one can buy valuable things only in dollars. If you need a valuable commodity, like oil, then you must have dollars to purchase it. The value of the dollar is derived from the demand for oil, and for the demand for dollars in which to trade with America, which is still the largest consumer economy on the planet.

These “twin towers” of demand for dollars – oil and trade – make the U.S. currency the most widely held reserve currency in the world. Having a reserve currency provides American policymakers and the Federal Reserve with advantages that their counterparts in other nations do not have. For example, it is easy to run persistent federal budget deficits and let the national debt exceed domestic GDP, so long as there are buyers for U.S. debt from recycled dollars from oil exporting nations (petrodollars) and exporters (e.g., China).

Reserve currency status gives governments more policy options, and political clout. Reserve currency nations can more easily sell debt, have more liquid and vibrant capital markets and have the ability to set interest rates and employ non-traditional monetary policy tools, such as quantitative easing.

As China’s economy transitions from an export-driven model to a consumer-based economy, Chinese policymakers want renminbi to become more dollar-like, giving them the ability to raise foreign capital, debt and currency reserves. The Chinese path forward is to reduce central control of the currency and begin the process of preparing the yuan to float freely in world currency markets.

Prior to the devaluation, the yuan was artificially held within a range relative the U.S. dollar, and post-devaluation, the yuan is closer to being valued on the fundamentals of the Chinese economy and demand for the yuan. China’s central bank said the yuan depreciation was a way to make the country’s financial system more market-oriented. The bank said market spot prices would now determine the daily position, implying that the central bank would step in less to influence it.

How “Free” is the Float?

In recent weeks, the yuan has continued to descend in value against the U.S. dollar. The yuan has weakened against the U.S. dollar at the fastest rate since the decision in August 2015 to devalue the currency. In January and February, the yuan’s erosion against a strong dollar prompted Chinese people to move money out of the country, which spooked its stock market, in turn spooking markets around the world. And now in a moment of déjà vu all over again, a plunging yuan is back as talk of raising U.S. interest rates intensifies.

The Chines government is sticking to rhetoric about the yuan being a free floating currency measured against a basket of currencies, consistent with messaging dating back to August 2015.

Bloomberg discussed the manner in which the yuan rate is set on a daily basis with the head of a Chinese bank: “’The 14 contributors, which must consider the previous day’s yuan closing price, have to take into account movements in baskets of currencies and have the leeway to consider the effects of client supply and demand,’ said Sun Wei, deputy general manager of financial markets at China Citic Bank Corp., a unit of China’s largest state-run financial conglomerate. He added that the People’s Bank of China spoke with lenders in February before standardizing the system.”

On May 23, 2016, the Wall Street Journal released an expose of sort revealing that the Chinese currency may not float as freely as many are led to believe: “China’s top leaders have lost interest in a major policy shift announced in a surprise move just nine months ago. In August 2015, the PBOC said it would make the yuan’s value more market-based, an important step in liberalizing the world’s second-largest economy. In reality, though, the yuan’s daily exchange rate is now back under tight government control.”

On Jan. 4, the central bank behind closed doors ditched the market-based mechanism, according to people close to the PBOC. The central bank hasn’t announced the reversal, but officials have essentially returned to the old way of adjusting the yuan’s daily value higher or lower based on whatever suits Beijing best.”

Altering directions to move away from a market based currency places the PBOC in the position of battling against downward pressure on the currency. The actions to voluntarily deflate the yuan by the PBOC are being received as an indication that the Chinese economy is slowing at a more rapid rate than anyone predicted.

It wouldn’t be shocking to acknowledge that the Chinese economy has slowed, but the extent to which it has slowed may be a point of contention. Hypothetically speaking, if the Chinese economy has slowed at a faster rate than global markets acknowledge, and the Chinese government is intent on avoiding a major crash or stock market fluctuations, it might make sense for the government to avert a bigger issue by voluntarily devaluing the yuan ahead of a potential catalyst that would push the Chinese currency and market down further, like a U.S. interest rate hike by the Fed.

A slowing economy will have large ramifications for the world oil markets as many producers are focused on Chinese consumption. And an economy on a faster downward trajectory than widely assumed could have a greater effect on a market mired in oversupply.

The Battle for Market Share Focuses on China

There have been a handful of geopolitical events in recent years that have highlighted the dangers of dependence on foreign oil to Chinese policymakers. In 2011, Sudan (and what is now South Sudan) provided China with 260,000 barrels of oil per day. That number shrunk to zero when civil war erupted in Sudan. China also lost some oil supplies when civil war broke out in Libya, cutting off crude exports.

In 2012, the international community (led by the U.S.) renewed and strengthened sanctions originally placed on Iran in 2006. The original sanctions were imposed in 2006 when the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1696 after Iran refused to suspend its uranium enrichment program. U.S. sanctions initially targeted investments in oil, gas and petrochemicals, exports of refined petroleum products, and business dealings with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

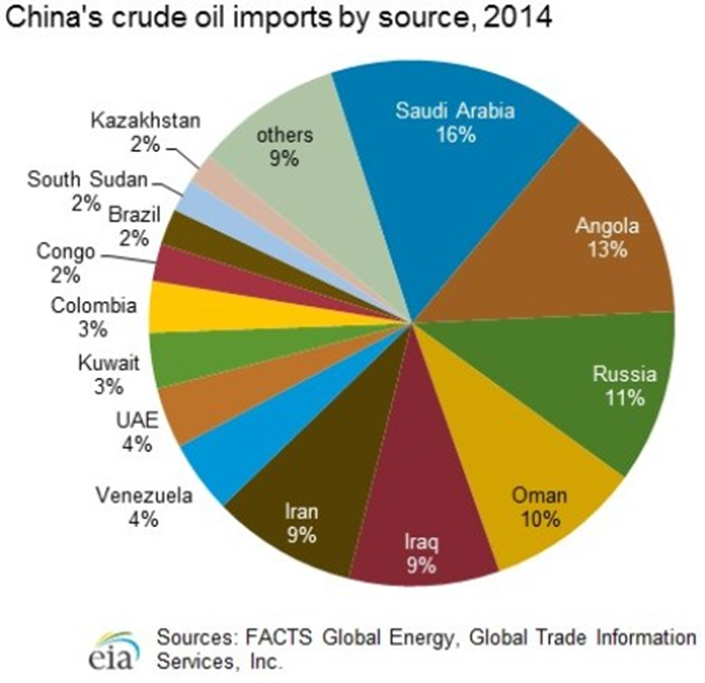

Before the sanctions, Iran was China’s third largest source of oil imports, providing 550,000 barrels per day in 2011, or eleven percent of China’s imports, according to the EIA. That figure dropped to 439,000 barrels per day in 2012. While that may not seem like a huge drop, it is important to remember China’s imports continued to climb over this period of time, requiring that country to find new sources of supply.

The U.S. government recently led an effort to mend ties with the Iranian government and reached a landmark deal with the Iranian government that has the potential to once again open up the opportunity for a flood of new supplies. China has taken full advantage of this proposed change and has already averaged a higher level of imports than before the sanctions affected the supply lines in 2012.

The increase in consumption of Iranian exports comes at a time when Saudi Arabia is producing at record levels. Saudi Arabia has eluded to the ability to ramp up production from these already elevated levels to compete with Iran and Russia for market share in China. The increased Saudi output needs to find a buyer, and China is the logical choice. Iraq too has increased exports to China as its output has increased in the last few years. Chinese oil companies – CNOOC, Sinopec, and CNPC – have taken upstream positions in Iraq, ostensibly increasing Chinese oil security.

China has been targeted by many of the oil superpowers as a logical choice to absorb some of the abundance of petroleum products currently flooding the world market. However, if the economic slowdown in China is going to be faster than originally believed, this could have a significant effect on the level of petroleum consumption.