Oil & Gas 360® recently interviewed John P. Englert, an environmental law lawyer with Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr LLP. Englert counsels a wide array of industrial and energy clients on environmental safety and health matters. In our interview with Englert, we talked about the Clean Water Act, and how some states are using it to block pipeline construction.

What is a CWA 401 Certification?

“When somebody applies for a Federal permit, in this case for a pipeline, they would be applying to FERC. If this project is going to impact waters of the United States, then they need to get a certificate from the state saying that the project will comply with water quality standards in the state,” Englert explained.

The Natural Gas Act of 1938 (NGA) gives FERC exclusive jurisdiction over pipelines that transport natural gas in U.S. interstate commerce.

However, states can throw in speed bumps by saying the project will negatively affect state waters by not meeting state standards.

Section 7

FERC also regulates interstate pipelines under Section 7 of the Natural Gas Act, this regulation prevents companies from building pipelines without FERC granting a certificate of public convenience and necessity.

“You need to have a certain amount of information, especially when you’re looking at wetlands and stream crossings, [and this is] where the 401c requirement becomes implicated on these kinds of projects, because the construction activity may involve crossing streams or wetlands,” Englert said.

However, to acquire this information, companies often need access to (private) property. Without permission, the application will lack information, pushing companies closer to deadlines and denial.

“In order to determine whether there are streams or wetlands that would be crossed, you need to have access to property to do surveys and to identify and delineate those areas,” Englert said. “A lot of times, a project can’t get access to do the surveys until they get their 7c certificate from FERC, and then they have to scramble to get the permit applications in, to get the permits in place.”

Looking back at Islander East – killed by Connecticut

Some may have forgotten, but Englert remembers the nearly decade-old Islander East Pipeline. The Islander East would have transported 285,000 dekatherms per day of natural gas from eastern Canada to Connecticut and New York consumers.

According to the Federal Register, the pipeline would have run about 44.8 miles from New Haven County, Connecticut to KeySpan Energy’s facility in Suffolk County, New York, and about 5.6 miles from Suffolk County, New York to a planned power plant in Calverton, New York. Connecticut pulled out the Clean Water Act.

“In Connecticut’s case, the [water] use was for fisheries and the state said that because of the potential impact from [pipeline] construction, it would disrupt the use of water for shell fisheries, and that was the basis for the denial,” Englert said.

The Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection (CDEP) denied the certification in 2004 and 2006, then the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld the second denial. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case, thereby ending the project.

The Big Apple

Constitution Pipeline

“In New York, they denied water quality certifications for different reasons. There, the state has claimed that they did not have sufficient information in the application to determine [environmental] impacts,” Englert said.

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) denied a CWA Section 401 Certification for the 121-mile pipeline that would have spanned New York and Pennsylvania. The company took the denial to court on the basis that the state had waived its certification requirement due to deadlines.

According to Law360, Section 401 of the CWA sets a deadline for state action – if a state agency from which an applicant for a federal permit “fails or refuses to act on a request for certification, within a reasonable period of time (which shall not exceed one year) after the receipt of such request, the certification requirement… shall be waived with respect to such Federal application.”

Simply put, the state has a year to respond, otherwise the FERC permit allows the company to proceed. However, in this case, the Second Circuit sided with NYSDEC, dismissing the failure-to-act claim by the pipeline company. A rehearing has been requested, and if the decision remains standing, then other pipeline projects could be affected.

The NYSDEC said that it conditionally denied water quality permits due to inadequate environmental reviews done by FERC. NYSDEC claimed that FERC “failed to account for downstream greenhouse gas emissions.”

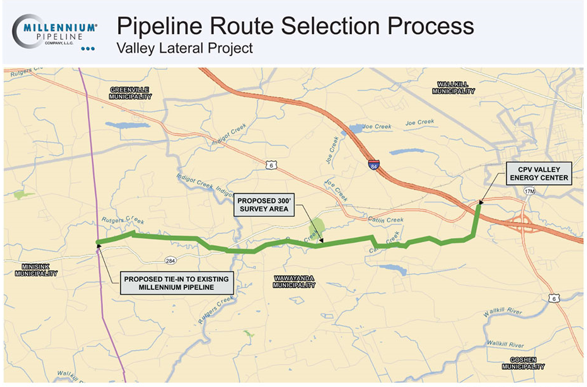

“[For] Millennium, [NYSDEC] stretched the field a little further, saying that the NEPA/EIS evaluation was not adequate to satisfy the state’s environmental quality review under the New York State Environmental Quality Review Act, the state equivalent of NEPA, so they seem to be migrating farther and farther from water quality and into other aspects,” Englert said.

Bring me a rock

Q: What happens when federal approval is gained, but state-level approval is not?

Englert: The scrum begins.

“FERC has weighed-in and has granted the certificate conditioned upon state approval and state permits, and in the cases we’re talking about, states have raised concerns and have not issued permits. Sometimes they extend the permitting process/cycle to get what they view as complete applications. In others, it seems that the state is exercising the applicants excessively to get more information,” Englert said.

“In military boot camp it’s referred to as “bring me a rock,” Englert said.

“You bring them a rock and they say, “not that rock, I need another rock.” It becomes what seems to be a never-ending process where you get information, you respond, and then they ask for more information. It’s frustrating to project developers.”