Last month, energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie came out with a warning: the world was running out of oil, but not just any oil. It was running out of oil that can be extracted with a low carbon footprint. The report shined the spotlight on an issue that tends to get overlooked in the daily discourse on climate change and the fossil fuel industry—the fact that not all oil is created equal.

Source: Oil Price

While it would be overly optimistic to suggest that any environmentalist would back an oil project, it might be worth considering the differences between oil projects that make some less polluting than others. Because in a discourse focusing exclusively on emissions, these differences matter.

Take the Willow project that President Biden approved earlier this month. The approval, which goes directly against Biden’s campaign promises to squeeze the oil industry, caused an expected stir among environmentalists. Yet some commentators pointed out that it might not be a certain disaster.

Indeed, like all oil projects in the United States, Willow will be subject to strict environmental impact rules, and there is no doubt these rules will be enforced enthusiastically. And this means that ConocoPhillips will make super sure it develops those resources responsibly and with as little emission footprint as possible.

Or how about gas flaring, which releases substantial amounts of methane—another greenhouse gas—into the atmosphere? Methane has been garnering growing attention from both activists and regulators, and this attention is beginning to produce results.

Exxon said earlier this year it had stopped routine flaring at its wells in the Permian and expressed hope that other producers would follow its example. Even if they don’t, however, flaring in Texas has dropped precipitously over the last decade or so –while oil and gas production grew in leaps and bounds.

Strict environmental regulation and the readiness to implement it can do wonders for an industry’s level of responsibility. Gas flaring and new drilling are only a couple of examples of this. So is carbon capture.

Last year, Canada’s biggest oil producers said they would spend some $16.5 billion on carbon capture by 2030. That sum would make up the bulk of a planned emission-reduction investment of $24.1 billion by the six biggest oil producers in the country.

Environmentalists don’t like carbon capture. In fact, many dislike it intensely, claiming it is too expensive to make economic sense and that it would only motivate more oil and gas production instead of depressing it.

The second part of this claim is probably true. The first—probably not so much, at least from the perspective of an oil producer. The industry is being hounded into virtually giving up its business because it is the new Devil. For that industry, carbon capture may very well become—or has already become—the means to survival, so they will gladly invest in it to reduce their greenhouse gas footprint.

In Canada, the Pathways Alliance, as the group of large oil producers has called itself, plans to capture and store some 10 million tons of carbon dioxide from more than 20 oilsands projects in northern Alberta. In Texas, Chevron is working on a carbon capture hub and just announced a plan to triple the size of the facility.

Again, these are just a handful of examples showing that not all oil projects are equal. Some are, if not better, then certainly less bad for the environment than others. Of course, the United States and Canada are not the only places where oil is being extracted responsibly.

The carbon footprint of an oil project also involves the purely technical process of extraction, which, depending on the geology, could be more or less energy-intensive and, as a result, emission-intensive.

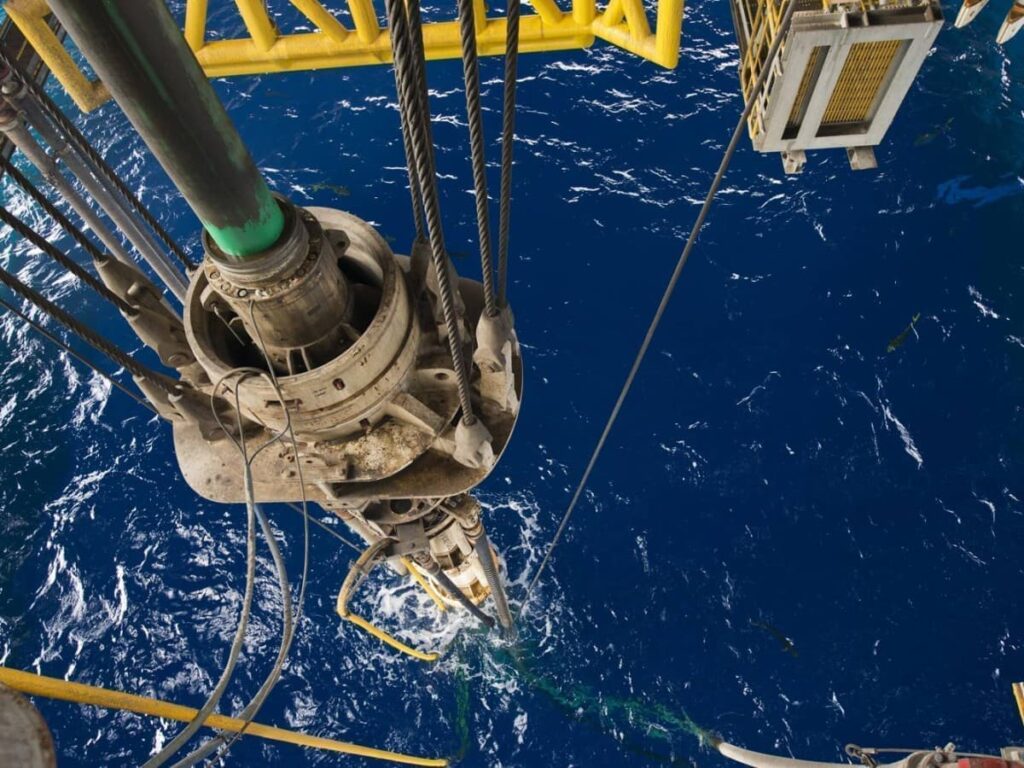

Take Guyana, for example. A new kid on the oil block, a tale of rags to riches in a few short years as Exxon and Hess make discovery after discovery offshore the tiny South American nation. Offshore oil is not the cheapest kind, for sure. Yet Guyana’s offshore oil breakeven level is around $30 to $35 per barrel. For Exxon’s second development site currently in operation, this has fallen to $25.

There is also Saudi Arabia—until recently, the world’s largest oil producer sporting the lowest breakeven prices in the world. As the emissions narrative gathered pace and volume, the Saudis have started adding to that the claim that their oil is also low-carbon—and that’s precisely because of that low breakeven. The less energy you use to develop a natural resource, the less emission-intensive that development is; it’s as simple as that.

Of course, it would be too much to think that any environmentalist activist would embrace low-carbon oil projects. The very nature of oil makes it the enemy of the activist. The only good oil as far as activists are concerned is the oil that stays in the ground.

Yet because the way the world works is far from perfect, oil continues to be taken out of the ground to be used in multiple ways, including for making the synthetic fiber used for the production of high-visibility jackets that environmentalist activists like to wear during their road blockades.

It might be wise to divert some of the attention focused on the oil industry from the fact of its existence to the ways it is changing to accommodate higher environmental standards—and reducing its emission footprint in the process.

By Irina Slav for Oilprice.com