From the Business Development Bank of Canada

Having remained stable in the low US$50s since December, crude prices plummeted by roughly 10 percent in the past week on concerns that recovering U.S. supply could derail the OPEC-led agreement to curb output.

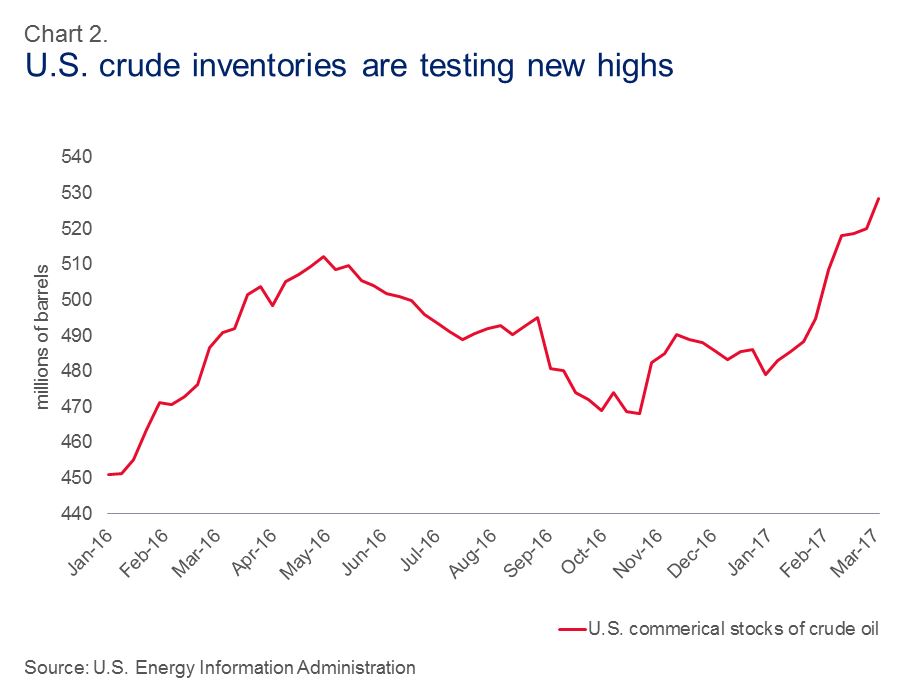

At the centre of these concerns, U.S. commercial crude inventories have hit new record highs for the past four weeks; however, markets appear relatively more balanced across a broader group of countries.

Notwithstanding the recent decline in prices, it is worth noting that little has changed in terms of market fundamentals. In particular, despite U.S. shale production being somewhat more economic than originally thought with crude in the low US$50s, world supply is likely to fall short of demand in the first half of the year.

Overview

Expanding U.S. crude production tests OPEC’s commitment to higher prices

Bolstered by the agreement between 22 OPEC and non-OPEC countries to cap supply, crude prices have remained remarkably stable since the deal was announced late last year. West Texas Intermediate, the North American light crude benchmark, traded between US$50 and $54 per barrel between early December and the first week of March, fostering a sense of relative market stability. This story changed somewhat on March 8, however, as a ninth consecutive weekly increase in U.S. inventories, coupled with a continued recovery in U.S. supply, caused prices to plummet (chart 1). The concern among market participants – validated this week in a statement by Russia’s energy giant Rosneft to Reuters – is that if U.S. production recovers too much, countries that agreed to cap production in order to support prices will no longer have any incentive to abide by the deal. Why should nearly two dozen countries slash output if the result is simply that U.S. producers gain market share?

Inventories swell in the U.S., but decline in other markets

Global inventories, in particular, deserve a closer look in terms of the market backdrop, if only to better understand the seemingly contradictory headlines since the start of the year. For instance, preliminary data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration shows crude inventories as having risen each week in 2017, and touching record highs the past four (chart 2). On the other hand, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has reported falling aggregate inventories1of crude and refined products since August of last year, with the notable exception of January – but not, based on preliminary data, in February (chart 3). So what is happening exactly?

First, it should be noted that it is not uncommon for U.S. crude stocks to rise during the early months of the year, as refinery maintenance ahead of the summer driving season causes throughput to temporarily fall. Second, depending on the port of destination, the shipping of crude alone can take weeks. Thus, crude exported from, say, Saudi Arabia late in the fourth quarter of last year – when production was high – would not appear in U.S. inventories until the first quarter of 2017. Finally, within the U.S. itself, petroleum production remains in the midst of a five-month comeback due to recovering prices. The extent to which this rebound will continue in the months ahead, despite what is likely to be a flatter price outlook, remains one of the big unknowns for oil prices. It is the risk of higher-than-expected future U.S. growth, and not the evolution of U.S. output thus far, that poses a far greater threat to the price recovery.

Market fundamentals remain largely unchanged

In short, it should be noted that the recent drop in prices – and rebound in U.S. supply – falls well short of constituting a radically altered market picture. In particular, the scale of the cuts agreed by close to two dozen OPEC and non-OPEC countries, at nearly 1.8 million barrels per day, are of an order of magnitude greater than the anticipated output growth south of the border in 2017. Rather, it is the risk that a bigger-than-expected rebound in U.S. production causes the agreement’s participants to reconsider future supply caps that threatens the global outlook.

The bottom line

The recent price downturn should be viewed more as an indication of market sentiment regarding the willingness of OPEC (and, to a lesser extent, non-OPEC countries such as Russia) to abide higher U.S. production, and less as an indication that the global supply and demand outlooks have changed significantly. While the production decisions of OPEC – and particularly Saudi Arabia – remain vital to overall price stability, current forecasts of fundamentals suggest that the gradual rebalancing of supply and demand should continue.