From the Grand Junction Sentinel

Oregon energy researcher and consultant Robert McCullough has done work in the liquefied natural gas realm while keeping an eye on the controversial Jordan Cove LNG proposal in his home state.

“We were watching the hubbub around Jordan Cove and I said, ‘you know, nobody really believes this is going anywhere. Why don’t we write down why?,'” he said.

Portland-based McCullough Research recently did just that, with McCullough and his colleagues penning a 10-page report to its clients questioning the economics of the project and giving it just a one-third chance of reaching the operational stage.

“Our analysis indicates that Jordan Cove will have a significant cost disadvantage compared to its competitors — approximately 25 (percent),” the report says.

He said he doesn’t think Jordan Cove, being pursued by Pembina Pipeline Corp., can beat out the LNG Canada project under way in British Columbia and the Cheniere Energy existing and planned projects on the Gulf Coast.

“In the end, it’s all going to be who can offer the lowest tolling fee, and these guys (Jordan Cove) clearly are not going to win that contest,” McCullough said.

Tolling fees are what buyers of the natural gas would pay based on costs such as liquefying it and getting it to them.

Jordan Cove is of interest to supporters of western Colorado natural gas development due to hopes that it could provide a long-term outlet for locally produced gas. While it also has some support in Oregon, others there oppose it because of concerns including impacts to the environment and to landowners along a proposed pipeline route in the state to serve it.

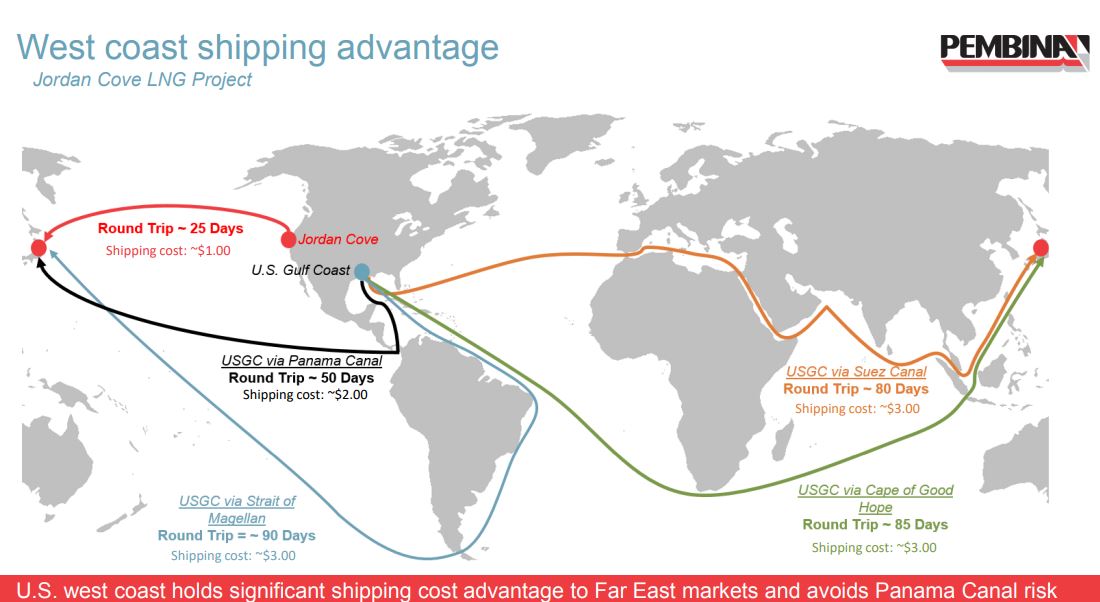

McCullough agrees that Jordan Cove has a big advantage over Cheniere because Gulf Coast LNG has a longer trip to Asia that requires a trip though the Panama Canal. But the Cheniere and LNG Canada projects are larger ones that benefit from economies of scale, he said. LNG Canada also has direct access to cheap gas from western Canada gas fields, whereas the price Jordan Cove pays for gas will be determined by the going price at the natural gas trading hub at Malin, Ore., where its pipeline would begin. That hub’s price is influenced by the fact that it serves California markets.

Jordan Cove also faces the cost of having to build a pipeline to serve it, a cost Cheniere isn’t saddled with, McCullough said. And Cheniere is close to electricity and experienced labor, he said.

Jordan Cove plans to use natural gas as the power source for producing LNG, whereas competitors are using cheaper and more reliable electricity, he said.

Jordan Cove spokeswoman Tasha Cadotte says the market feels different than McCullough about the project’s economic viability, as evidenced by the fact that Jordan Cove has nonbinding commitments from buyers for 11 million metric tons per year of LNG. That’s more than the project’s planned annual production capacity.

“The combined benefits of cheaper gas supply, shorter shipping distances, and the lack of reliance on the Panama Canal have made (Jordan Cove) competitive with LNG projects around the world, including the U.S. Gulf Coast,” she said.

Eric Carlson, executive director of the West Slope Colorado Oil and Gas Association, said he doesn’t know the LNG business well enough to say whether Jordan Cove is a good investment or not.

But he said it makes sense that it offers cheaper shipping costs than for LNG coming from farther east and going through the Panama Canal. He also said what he hears is that there is a huge market for LNG in Asia and Europe.

“It may be that there’s enough space available and market availability for sort of all of the above — all these LNGs (facilities) that are being proposed, there might be potential” for all of them to be built, he said.

Pembina recently said in a news release that it continues to consider Jordan Cove to be viable but is limiting capital investment on non-permitting-related activities until it makes a final decision on whether to go forward with it.

It said it has approved “incremental funding” of about $50 million this year in support of regulatory and permitting work.

Cadotte clarified in a recent email that the $50 million is in addition to $100 million it had previously said it planned to spend this year on the project, rather than being a $50 million reduction in that spending. She said the $100 million already has been spent.

Notably, Michael Hinrichs, who has made multiple trips to western Colorado as spokesman for Jordan Cove, is no longer involved with the project. Cadotte said his departure from Pembina was voluntary. Reached by phone, Hinrichs also said it was voluntary but declined to further discuss the reasons behind it.

He said he is still doing public affairs consulting in the western United States.