Drilling but not completing wells–why is it done?

The uncertainty of the last year and a half surrounding the oil and gas industry has given rise to a multitude of different rationales about industry practices. Rig counts have been dissected, production levels followed, and any data point that could possibly be related to oil and gas has been factored in. Big data all the way down to minutia has become conversation points for oil and gas observers. Among the most mystifying data points being processed is the inventory of drilled but uncompleted wells–DUCs.

Drilled but uncompleted wells (DUCs) have garnered a lot of attention, and for good reason. They represent a massive source of uncertainty regarding price direction and U.S. supply, and their overall impact is completely unknown. Some argue they are overhyped because of logistical and economic barriers, while others believe they will bring about a gusher of supply at a moment’s notice.

The downturn in commodity prices has led many to hypothesize that the costs associated with well completions have driven many companies to actively drill the well and leave it uncomplete to conserve cash flow and back stock production for a later date. However, new data from Bloomberg Intelligence may add a new wrinkle to that theory.

There are several reasons why a company would choose not to complete a well. Cost would certainly be a factor, availability and contracts on rigs and frac spreads, the economics of a well and potential return, and commodity prices.

Limitations on capital spending in 2015 and 2016 have cut down on the number of news wells being drilled and completed. The constraint on spending would lend to the rationale behind the desire to not complete a well, completions can account for up to 75-80% of the well cost. Depleted commodity prices are also believed to factor in. With lower prices, the IRR for a project would decline as the price dips. Companies may make the decision to limit their capital costs by only drilling a well, and wait until prices improve and IRR rebounds to complete the well and start producing. This would mean companies are essentially storing their oil in the ground instead of a storage tank.

Analyst Jeb Armstrong has a different theory on DUCs, as he told Oil & Gas 360® in an interview last year: “The only reason why I can see a company willingly drilling DUCs is because they have a rig contract that’s too expensive to cancel. Might as well keep the rig operating and plow the capital into the ground than pay a penalty to the rig owner.”

Raymond James explains that the “frac crews” are an important factor; most are contracted on a job-by-job basis, while rig contracts can last years and include penalty fees if the operator chooses to break the contract. A further explanation includes: “As operators were faced with cycle-low pricing they were forced to decide between A) laying down rigs and taking the capital hit as a result or B) continuing to drill wells until the contracts rolled off. On the whole, we believe many E&Ps chose the latter option; deciding to drill these wells at near-or-below breakeven pricing and deferring the completion (and thus production) for a later date.”

Drilling but Not Completing: the Uncompleted Trend

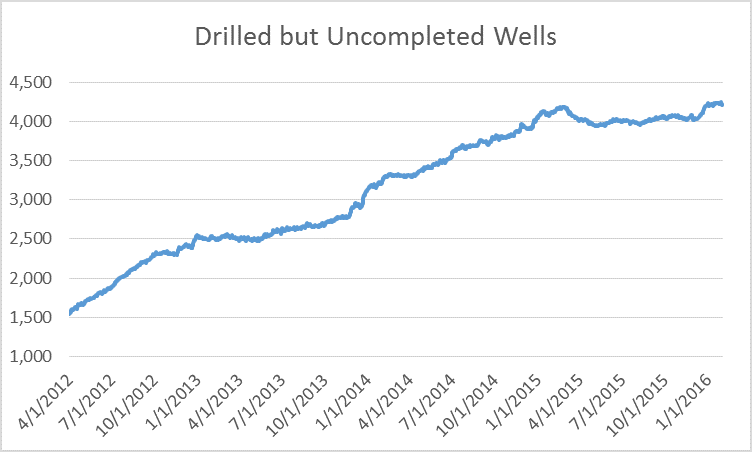

The data trend for uncompleted wells would lend itself to the two ideas presented by Armstrong and Raymond James. Drilled but uncompleted wells continued to increase from April 2012 until the end of 2014. Between November 27, 2014 and February 1, 2016, the number of DUCs increased by 253 from 3,966 to 4,219. For comparison, the number of DUCs increased 840 from the beginning of 2014 until November 27, 2014. When oil prices started their long slide in November 2014, many producers kept drilling wells, but halted expensive fracking work that brings them online, presumably waiting for prices to bounce back. However, the majority of the fraclog was already in place.

The fraclog was largely built up over a period of time when oil prices were in the $90 to $100 range and has curtailed since the commodity prices began declining. The comments from Raymond James and Energy Directions point to the continued increase in DUCs over the last year and a half, but what was the driving force behind the continued build of DUCs leading up to late 2014?

The Constraints of Infrastructure

There are two components to drilling and completing a well, as the term suggests. A rig must first drill the well, and then a frac spread is utilized to complete the well. This necessitates two different equipment outfits and two separately skilled crews on the well site. The dichotomy of this practice highlights another distinction in the growth of DUCs.

As the oil prices have declined, rig counts have fallen off dramatically as well. Drilling rigs have been laid down as the economics of drilling dwindled, waiting for prices to rise again to reinstate drilling programs. A key indicator of this was rig count, which declined from 2,086 in Q4 2014 to 430 rigs as of June 10, 2016.

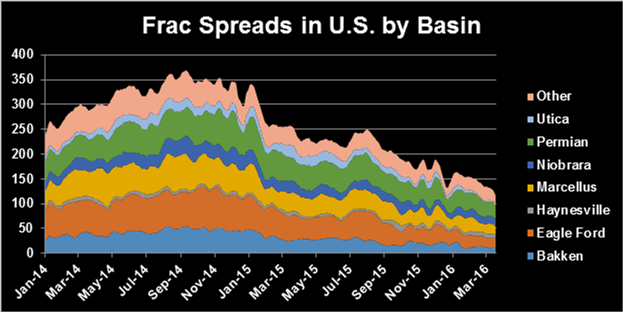

The decrease in rig count would account for the plateauing in the DUC count. The decrease in utilization of active rigs would mean fewer wells are being drilled. In the same vein, there has also been a decrease in the use of frac spreads over a similar time. As shown in the chart below, the number of frac spreads by basin has decreased in a similar manner to rig count.

One data point that is worth noting. During the fourth quarter of 2014, both the rig count and the number of frac spreads were near a high, rigs hovering around 2,000 and frac spreads around 350. This is a rather glaring difference between the resources available to drill a well and those available to complete the well, an almost 6 to 1 ratio.

Assuming that the drilling time takes twice as long as the completion time or that drilling takes 2/3 of the total drilling and completion time (which is very conservative towards drilling time), that would still place the ratio at 3 to 1. With three times the amount of drilling rigs in use as frac spreads, it is no wonder the DUCs have continued to stack up.

Economics of Different Plays

Observing the dwindling rig count falling almost in lock step with oil price would lead to the logical conclusion that economics are a driving force in the DUC tally. And there is certainly merit in that idea. Companies will not choose to increase drilling capacity and increase capital expenditures without a viable return on the output. That being said, the increase in DUCs per basin may give a unique insight into the increase in DUCs in some basins.

The chart below highlights the number of DUCs in four of the most prominent oil basins in the U.S. The number has been indexed to 100 starting at November 27, 2014 (the day that OPEC decided to hold production steady and tank oil prices) to show the increase or decrease in DUCs from that point forward.

The largest decrease in DUCs has come from the Eagle Ford play located predominantly in Texas. The largest increase has come in the Niobrara, which compared to the Eagle Ford is a relatively new play, at least for horizontal development. Though they were currently not a leader in developing horizontal drilling in the basin at the time, Synergy was a fast follower and commenced its operated horizontal drilling program in May 2013 with a rig on its Renfroe lease in the Wattenberg Field.

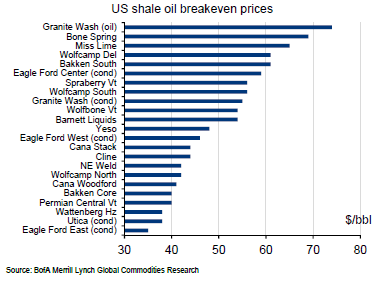

To follow the train if thought above, it would follow that the Niobrara and Bakken have more difficult economics to generate a return than the Permian and Eagle Ford. However, according to data from Bank of America Merrill Lynch in the chart below, the Wattenberg (the field that is home to the Niobrara formation) ranks as the third lowest breakeven cost within the U.S. shale plays. Parts of the Permian and the Eagle Ford rate very high as well, while the Bakken economics lag behind some of the other plays.

The economic argument would hold water relative to the Bakken, where the basin economics are less favorable. But the data point that sticks out is the economic feasibility of the Wattenberg/Niobrara. As one of the plays with better economics, it would follow to ask why the DUCs continue to stack up in this region?

In the chart above highlighting frac spread counts, the thin dark blue line running through the middle of the chart is frac spreads in the Niobrara. On average over the last two years, the Niobrara has been home to an average of 8% of the total frac spreads. Whereas the Permian and Eagle Ford have held roughly 40% of the total frac spreads.

Granted, the total well count in the Permian and Eagle Ford is far greater than wells in the Niobrara. The infrastructure limitations that are present in the Niobrara are one of the driving forces behind the increase in DUCs in that region.

Onward and Upward

The attention that oil price has garnered will not be letting up in the near future, it may very well intensify. Part of that attention will be focused on the unknown effect of the DUCs that are sitting and waiting around the country. Eliminating the drilling component shortens the time that these wells need to come online with production.

The increase in DUCs has been a result of several potential factors including economics, contracts, and infrastructure. The constraints of infrastructure have played a big role in the smaller plays, increasing the number of DUCs in those basins.

Looking ahead, the same constraint is likely to restrict the dwindling of the DUC count assuming oil prices continue to rise and more well sites gain economic feasibility. Limitations from the number of frac spreads and the crews to man them will limit the number of wells that are completed. Oil service companies have not been immune to depletion in prices and have laid off workers and limited the number of frac spreads and crews in service, and there will almost certainly be a lag in ramping back up to previous levels.

The number of DUCs will likely come down as the oil price ramps up as there are restrictions in lease agreements and requirements of the state that wells be drilled in a timely manner. Also, having the drilling already finished will limit the future capital outlays to get the well producing. But the limitations of infrastructure will limit the effect of DUCs on overall production levels, there will be no flash flood of oil coming to market as DUCs reached completion.