Your Competitive Edge Starts Here

With Oil & Gas 360 Premium Access, you’ll always be the first to know—get the intelligence that drives innovative strategies, faster decisions, and better results.

What You’ll Unlock with Full Access:

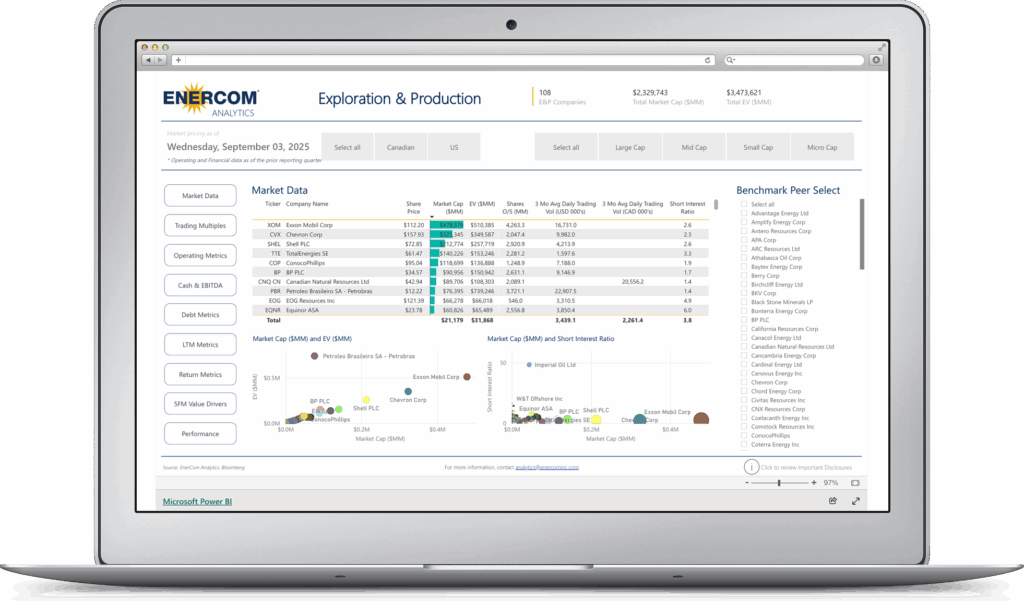

- Marketwatch & Valuation Dashboards: Stay on top of company stock prices, charts, trends, news, company filings, projections, contact information, and valuations.

- Daily Industry News & Insights: Real-time industry news, insights, and opinions.

- Conference Presentation Replays: Learn from the leaders shaping the energy industry.

- Webcasts and Earnings Conference Call Details: Never miss the conversations that matter.

Premium Monthly Subscription

$59.99 / Month

Valuation & Benchmarking Dashboards

Marketwatch Stock Data

Earnings & Events

Conference Replays

Industry Insights & Opinions

Premium Yearly

$599 / Year

Valuation & Benchmarking Dashboards

Marketwatch Stock Data

Conference Replays

Industry Insights & Opinions

Earnings & Events Calendar

Save $120 by subscribing for a full year

Annual Corporate Membership

$3,490 / Year

Valuation & Benchmarking Dashboards

Marketwatch Stock Data

Earnings Events & Calendar

Conference Replays

Industry Insights & Opinions

Subscriptions for up to 10 company employees