(BOE Report) – NEW YORK (Reuters Breakingviews) – Oil fields are just as quick to make fortunes as break them. The 1901 Spindletop gusher in Texas jumpstarted the petroleum age, crashing oil prices. A mere two years later, over-extraction drove the field into decline. Sure, today’s industry is far larger and more sophisticated.

But even in the mighty Permian Basin, which turned the United States into the world’s biggest oil producer, resources eventually deplete. There are signs that the peak is already at hand.

Twenty years ago, the U.S. produced about 5 million barrels of crude oil per day, down by half from the 1970s. With even remote fields like Alaska’s North Slope sputtering and the cost to find and extract an additional barrel of oil rising, collapse loomed.

The turnaround came when engineers figured out how to inject a mix of water, sand and chemicals at extremely high pressure into shale formations, cracking them apart to reveal the natural gas and oil deposits within. This proved fruitful in fields from North Dakota and Appalachia, but perhaps nowhere more so than the Permian in Texas. This field alone now produces over 6 million barrels per day, nearly half of the nation’s current production and more than the entire country produced before the technological revolution.

While that approach, known as fracking, opened up vast new reserves, it has not upended the basic laws of economics. There is a cost to pulling black gold out of the ground. If market prices for it fall below those expenses, drillers will pull back. According to a survey of oil companies by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, this break-even point is around $61 per barrel in the Midland Basin, the heart of the Permian, and $65 for the region as a whole. The market price for West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the widely used benchmark, currently hovers at around $62.

That might not be existential. What matters to most drillers is the expected price of oil over the lifetime of a well, rather than right now. The fear is that the recent, sustained downswing in WTI prices indicates diminishing expectations of future demand – particularly important for the Permian, which has effectively become the world’s swing producer, able to ramp up or dial down production quickly as conditions change.

That sensitivity may mean muted future output. The International Energy Agency predicts annual global demand for oil will grow less than 1% this year. Over the long run, things look even grimmer. China accounted for roughly half of all global oil demand growth over the past two decades. The rise of electric vehicles there already has slowed growth to a crawl, and threatens to destroy demand. With a shift to battery power incipient elsewhere, the IEA predicts global oil demand will peak before the end of the decade, leaving a surplus of supply.

While demand predictions should be taken with a grain of salt – as gyrations during the pandemic showed – it’s harder to escape rising costs in the Permian. That $62 per barrel break-even price in Midland is up from $46 in 2017. Tariffs on crucial materials like steel will increase these costs further.

Operating costs are not yet high enough to threaten existing wells, plenty of which are profitable at current prices. The Dallas Fed survey indicates that it would take a further 50% cut to the price of oil before it no longer made sense to keep pumping.

Snag is, shale wells have an extremely short lifespan. On average, production drops by more than two-thirds after one year and 95% after six years. So if new wells begin to look like a bad bet, that will show up in overall production numbers quickly.

Of course, average figures belie the wide differences in the quality of land from one patch to the next. Problem is, the best spots are running out. On so-called tier-one acreage in the Permian, drilling can generate a 30% return, based on net present value, at $50 a barrel oil. That’s enough to cover operational risk, service debt and pay dividends. This prime real estate could run out in about 3.5 years, reckons research outfit Enverus.

That’s not the end of the world; there’s another 3.5 years worth of oil that clears the hurdle at prices of $55. But put all of this together, and it’s enough to make some of the earliest champions of fracking increasingly bearish. Harold Hamm, who made billions by pioneering the practice in North Dakota, said at an industry conference in March that U.S. crude production was beginning to plateau. Scott Sheffield, founder of Pioneer Natural Resources, said in a CNBC interview that one of the main reasons he sold the company to Exxon for $65 billion in 2023 was that it was running out of tier-one inventory – and that everyone else is, too.

The Permian’s future might have already been spelled out. The Bakken Formation, largely in North Dakota, birthed one of the earliest fracking booms. Production increased from roughly 90,000 barrels of crude a day in 2005 to 1.5 million in 2019. As costs rose and tier-one and -two acreage expired, North Dakota’s production has declined by nearly a third since.

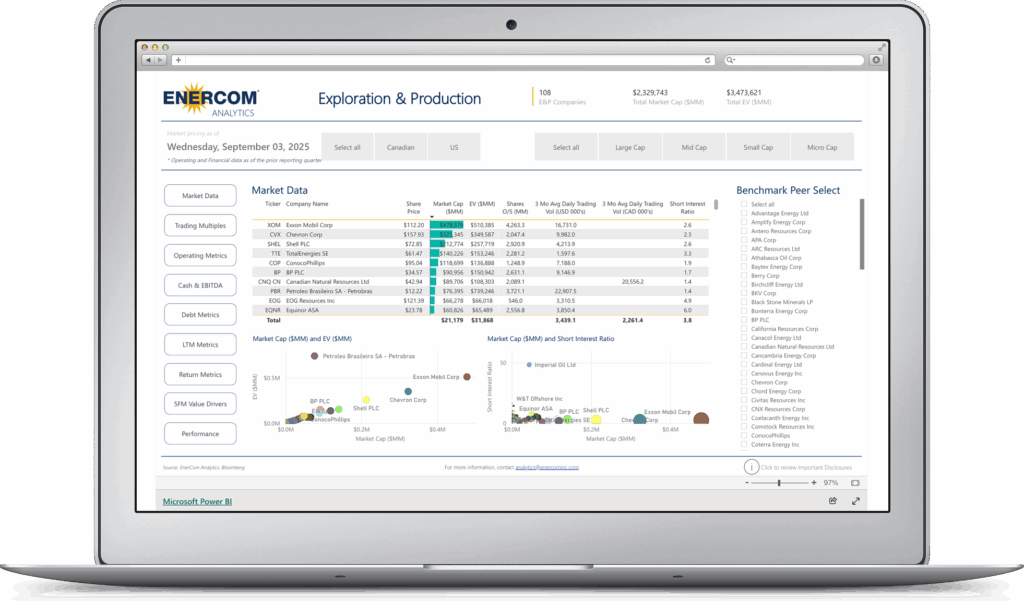

The biggest energy firms are already in capital preservation mode, preferring to send cash back to shareholders. The top five Western extractors – Exxon Mobil, Chevron, TotalEnergies, BP and Shell – spent about $225 billion, a record, on share repurchases and dividends over the past two years. Investment in new production stagnated. To add to the foreboding, cash flow from operations didn’t cover the combination of capital expenditures and cash returned to investors at either Chevron or Exxon in the first quarter of this year.

Of course, even if the peak is already here for the Permian, it will – like the Bakken – keep pumping for years. But the effects on U.S. policy could still be substantial. As both the world’s biggest producer, and consumer, of oil, fights over fossil-fuel dependence have been intense. Even amid the dramatic rise of electric vehicles or renewable energy, politicians on both sides of the aisle have tended to favor rising production. If the Texan spigot starts to slow, and the U.S. economy tilts toward consumption, that may favor policies that favor decarbonization, if only to offset risks to national security. The last oil crisis served as a spark for all kinds of novel energy ideas. Such a change in the political economy would be the industry’s biggest risk of all.

Follow @rob_cyran on X

(Editing by Jonathan Guilford and Pranav Kiran)