In Part I of this exclusive interview for Oil & Gas 360®’s “Top Minds in the Business” series, legendary oil man Bill Barrett shares his views about wildcatting, his history as a successful wildcatter in the Rocky Mountains and what to look for in building an acreage portfolio.

Credit: SEUEPA

There are some business people who stand out in any industry because they achieve an unusual degree of success, most often from a track record of good decision making, a high-level instinct for the business they’re in, and the ability to recognize a good opportunity and move fast to take advantage of it. William J. Barrett helped set the bar in the oil and gas business. Bill Barrett is a legendary oil man in the Rocky Mountains who is known worldwide for creating successful companies, unearthing discoveries and creating prosperity from exploration.

Mr. Barrett’s accomplishments include being presented with Outstanding Explorer and Lifetime Achievement Awards by industry associations including the American Association of Petroleum Geologists. He was honored with two of the highest awards by the Independent Petroleum Association of Mountain States, receiving the Wildcatter of the Year in 1993 and being inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2003.

Oil & Gas 360® spoke to Bill Barrett from his home in Denver regarding the past and present of the oil and gas industry.

OAG360: Could you take us through the evolution of the companies bearing your name?

BILL BARRETT: After earning a degree as a geologist from Kansas State University, I worked for several oil and gas companies—El Paso Natural Gas, Pan-American Petroleum and Wolf Exploration—before I partnered with Chuck Shear to form our own company in 1970. We eventually merged with Rainbow Resources and sold it to the Williams Companies in 1978 for about $40 million.

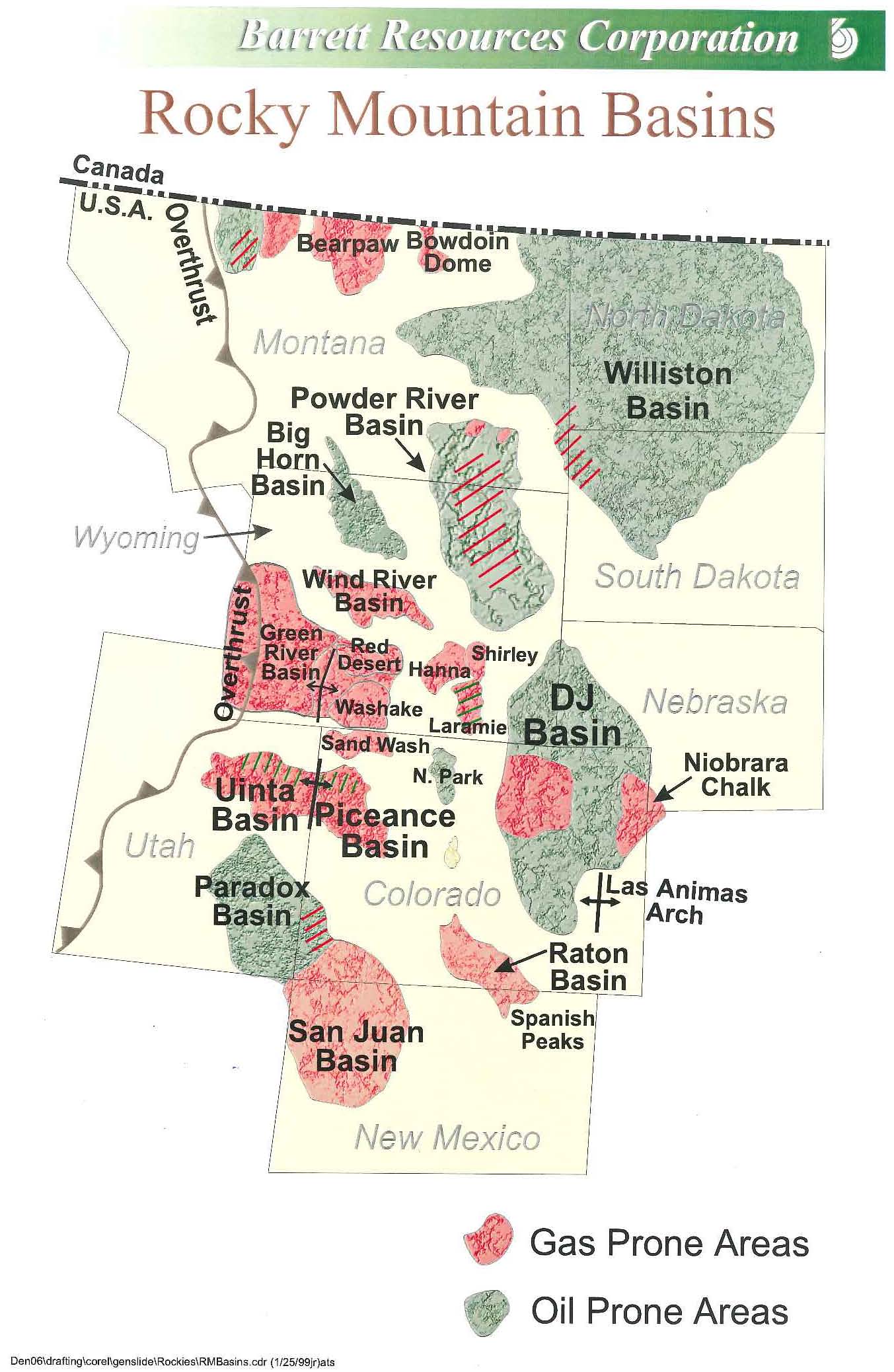

But the first company that had my name was Barrett Resources. That was in 1981. When we sold our previous company to Williams, we had to sign a three-year non-compete agreement. We had about four million acres all over the Rockies, but the one place we were not in was the Denver-Julesburg (D-J) basin.

One of the discoveries in the D-J was the Wattenberg field. It had been discovered about nine years before I got involved. It looked like it had quite a bit of potential, especially on the north and west side.

Amoco had discovered the field and had taken 10-year leases there, but they had less than one year remaining on those that weren’t held by production. So we went in and top leased everything we could get our hands on in the Wattenberg, which turned out to be about 40,000 acres. We got everything except a 60 acre tract. We also got a nuclear plant, which had never been leased, and were able to put about 40 wells on it. So we ended up drilling about 200 wells in the Wattenberg, and we realized there was potential in the Niobrara and Codell, along with the J-sandstone.

While this was going on, Amoco started using massive frac technology. I was an Amoco guy so I knew most of the geologists, and we were all pretty good about sharing whatever information we had. The Wattenberg is definitely more of a technology play. Niobrara was more shale, the J-sand and Codell were tight sandstones, and everything was vertical; we didn’t have horizontal drilling then. You were basically doing what they do horizontally now, except we were just doing it vertically.

OAG360: What else was in your portfolio?

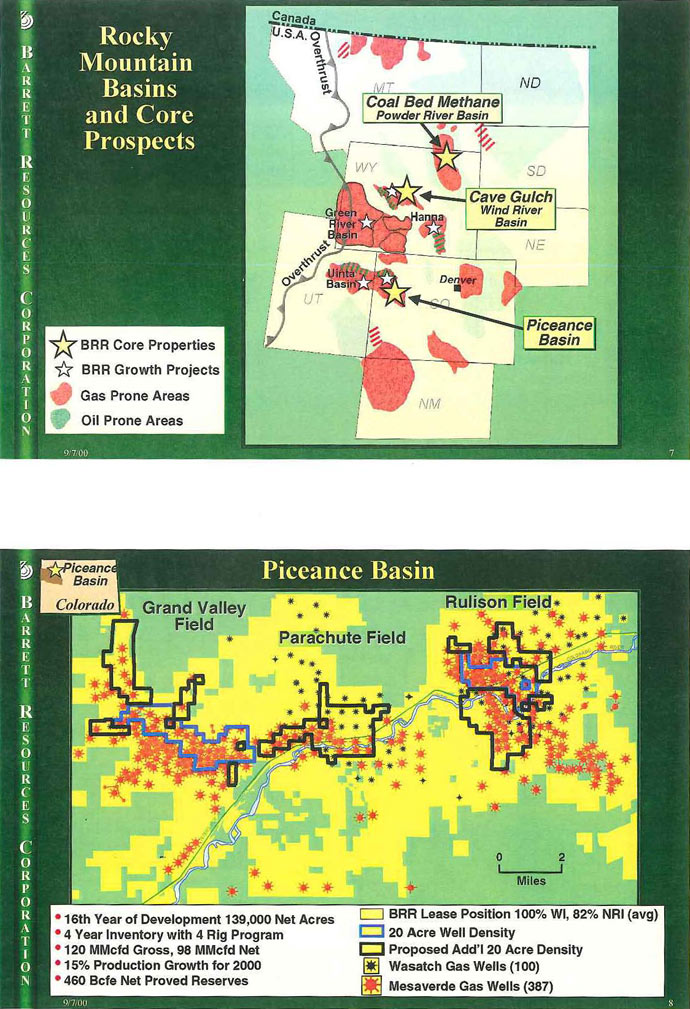

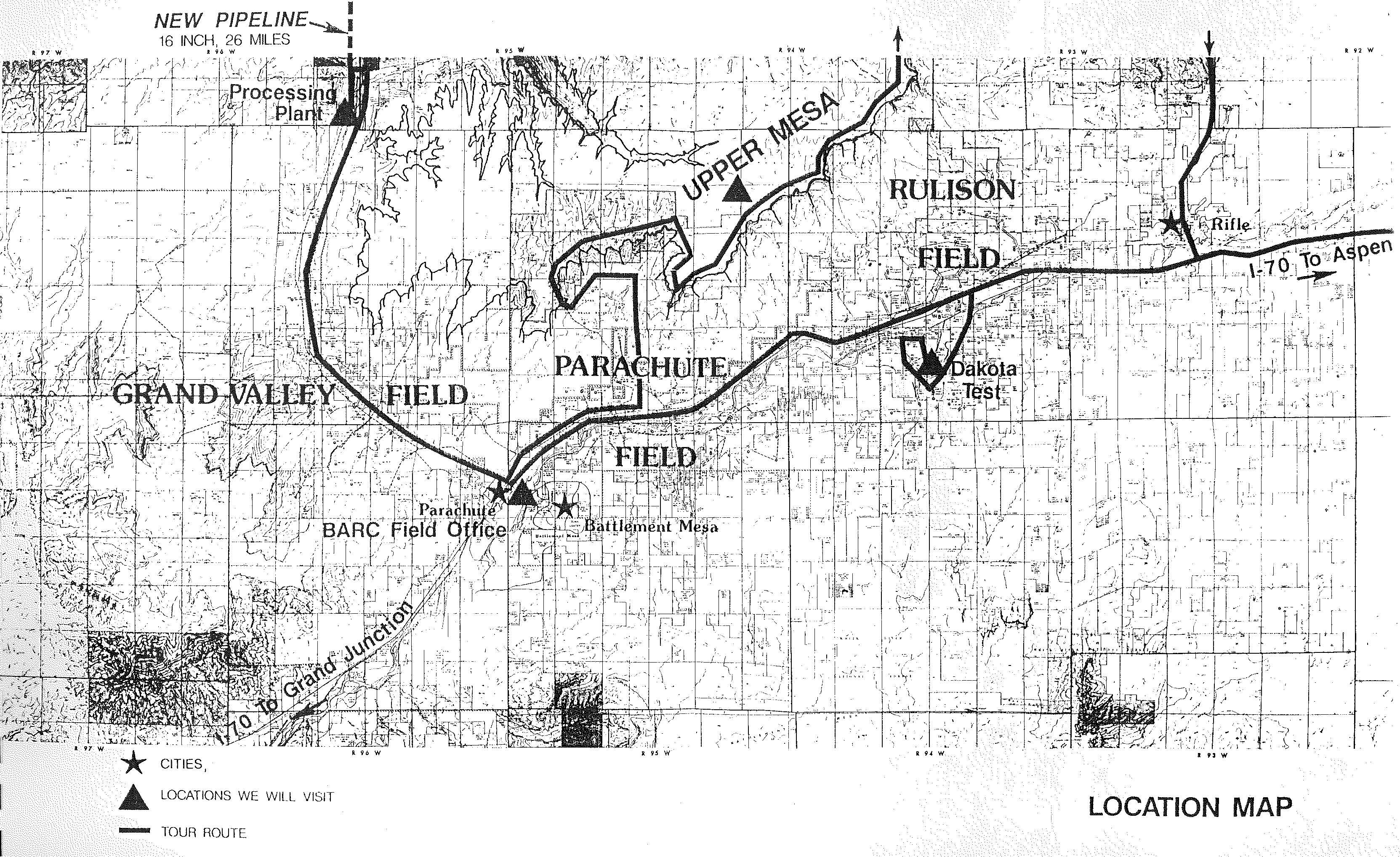

BILL BARRETT: At the same time that was going on, we assembled about 40,000 to 50,000 acres in the Piceance. We sold three-fourths of the prospect and kept 25% interest. We were able to sell them for about $7.50/acre after we bought the leases for $1 to $2 per acre. Eventually we ended up discovering the Parachute and Grand Valley fields over there.

In the Wattenberg, the Codell and Niobrara took off; you just couldn’t drill a dry hole in the damn thing. All the funds were wanting to get involved because it was so low risk, but the gas prices were pretty pathetic at the time. We got an offer on our Wattenberg properties from Snyder Oil that we couldn’t refuse, so we sold that and took our massive frac technology to the Piceance; and that’s where we made the money.

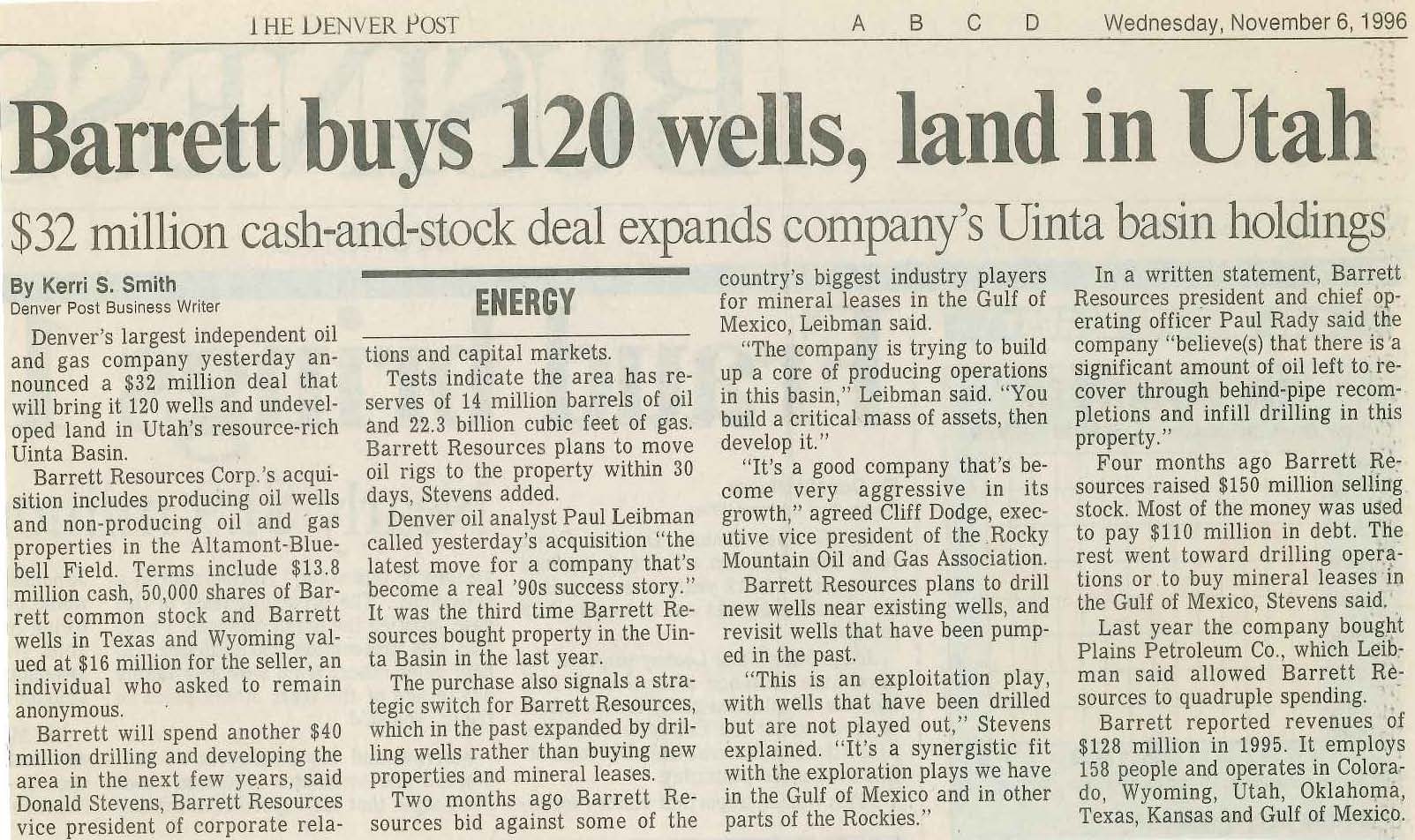

We drilled our first well in ‘84, but then oil cratered in ‘86. During those blood baths, you certainly have an advantage to make mergers and acquisitions. In the downturn, a lot of our partners became discouraged and we had to shut in some wells, but we ended up buying out all of our partners. It took three or four years but we did it and had 100% working interest in more than 130,000 acres. We bought another field nearby, called the Rulison, from Williams, which was kind of strange because we ended up selling it back to them in the long run. But in all of our positions, we ended up having 1 Tcf of proven reserves, 3 -4 Tcf of Proved, plus Probable, plus Possible reserves (3P), and that was well before the advent of horizontal drilling. That’s when Shell realized the situation and they made an attempt at a hostile tender offer. In the end, we sold Barrett Resources to the Williams Companies for $2.4 billion in 2001.

OAG360: Was the Piceance your calling card or did you have other properties?

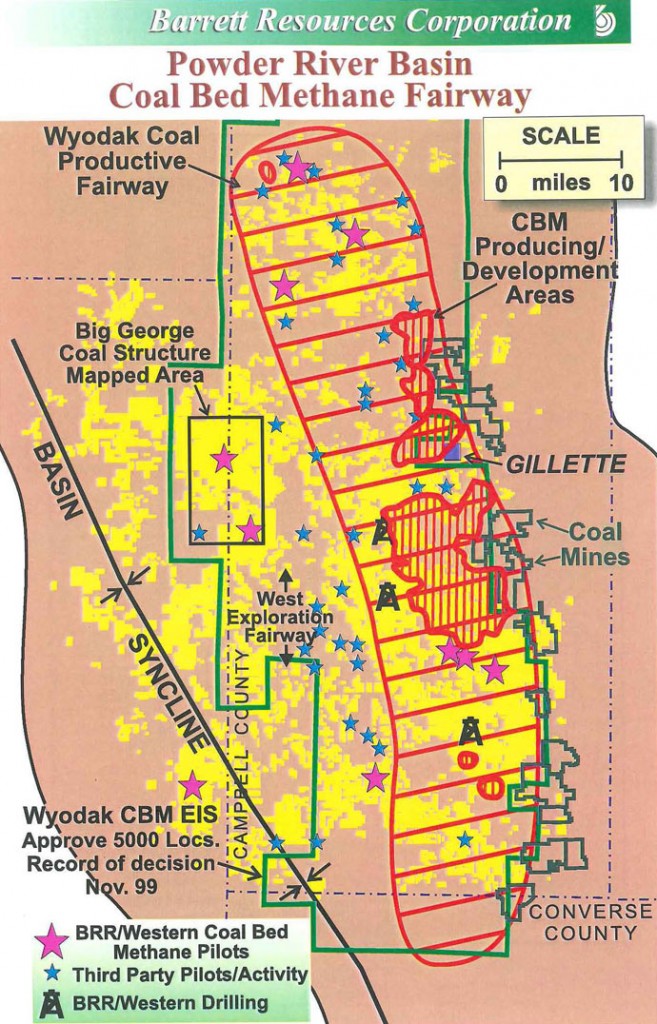

BILL BARRETT: We had the Powder River Basin (PRB) also. A marketing guy walked in my office one day and said, “There are a couple independents who have been trying to complete the Fort Union coals up in the Powder River, but they’ve been working on it for several years.” We had never paid much attention to them, but once he told me that, we jumped in and mapped out the coals and discovered the potential. It was a very active area, so it wasn’t too difficult to find some information. We made an offer to two independents for $20 million, but we got beat by an offer from Western Gas for $22 million. We were disappointed we didn’t get the extra land, but we already had a position in the region and decided to go ahead with the acreage we already had.

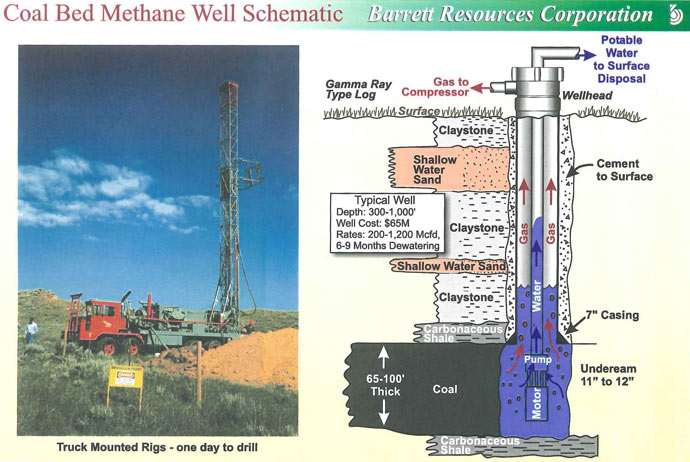

Next day, the CEO of Western Gas offered to go in for a joint venture as 50/50 partners, but we had to develop the coalbed methane play. That worked out fine, considering that was our plan anyways. Western gas was more of a pipeline and processing marketing company, which was important in reducing the coalbed methane gas via compression. So we made a deal and ended up acquiring more than one million acres long term and became the largest coalbed methane producer in the PRB. We each ended up with a little over 2 Tcf of gas reserves, so that made us even more attractive to buyouts. If I had to do it over again I may have been a little more selfish, but it just wasn’t a popular play at the time. Coals are a different breed of cat. You had to dewater them and they’re very shallow (about 300 to 600 foot wells), but the PBR wasn’t even ranked as one of the major plays when we got started. But after about four years it was ranked the number one gas play in Wyoming.

OAG360: Do you think the glory days of wildcatting are over?

BILL BARRETT: You have to define wildcatting. The glory days in the Rockies and probably in the U.S. of true rank wildcat drilling meant really one thing—that you just didn’t have any wells.

Those days are over. You used to call a wildcat well any well that was one mile from existing production. If you were drilling a step-out [well] in an area with space, that was a development well, but if you stepped out over one mile, they’d call it a wildcat. So there’s a great deal of leeway in what you call a wildcat.

So when we discovered production in the Piceance Basin, we drilled five wells out there in an area that covered about 500 square miles but never had a well in it. That was true wildcat drilling. That type of drilling in the Rockies is pretty much over – there’s too much drilling and too much control. Of course you still have wildcatting in the Gulf of Mexico and throughout the world, so conventional wildcatting is still going on in other places, but with all of the horizontal drilling in the shales, wildcatting as we knew it back in the 1980s is pretty much over.

OAG360: Why did you choose the Piceance?

BILL BARRETT: How we approached drilling was you had to go into a basin.

The Piceance is kind of connected to the Uinta basin which is a huge sedimentary basin separated by the Douglas Creek arch, basically on the Colorado-Utah border. I always made it a priority to map the total basin and you learn all you can geologically, along with existing production, and try to determine where potential plays exist within the basin.

One thing that led me to the Piceance was that early in my career I worked with the El Paso Natural Gas Company, and after about two years in Salt Lake City they moved me to the San Juan Basin (SJB), which was a new development. At the time they were developing the Mancos and Dakota formations, and it was turning into a huge gas province. At the time it was the second largest gas play in the US. So early on, we were drilling 200-300 wells per year and I was doing a lot of geology.

Then I was exposed to the Piceance and saw a lot of similarities from the SJB, so I did a lot of detailed geology and it appeared to me that there was a gas trap in the Piceance just like in the SJB. Everybody realized the Williams Fork contained a huge amount of gas in place and was quite tight, but no one ever came up with the key to making it commercial.

In fact, the government set off a couple of nuclear bombs in the area as a way to fracture the ground and make it more commercial. Unfortunately the gas ended up being radioactive and it turned the reservoir rock to glass, but the bottom line was that people knew there was a huge amount of gas in place.

So, long story short, we could not put a good lease position together because, at the time, a lot of the lease positions were held by the larger companies and they were being held for the Green River oil shales. There was huge potential in those shales, so you had companies like Exxon and Cities Service (Citgo) and Union Oil of California holding those leases, so it was difficult to get meaningful lease positions because they were in the guts of the basin.

So about 1983, Exxon decided that the oil shale was not going to be economic and they had spent several billion dollars on development. They even built the town of Parachute, Colorado, over there. So on a day that the locals called “Black Friday,” Exxon decided to exit the shale and that created an opportunity for us to put together a lease position, and we got 40,000 acres. We turned the prospect and retained operations along with a 25% interest in the play.

So then we drilled five Piceance wells which led to the discovery of the Parachute and Grand Valley fields. It’s just about that time you had the downturn in 1986, when oil prices went completely downhill, worse than today, and gas prices were already in the tank. In the summer gas prices dropped below $1.00/Mcf and we just shut our wells in.

So we went ahead and started developing the field using massive frac technology, completing an 1,800 to 2,400 foot sequence on Williams Forks type sandstones, and we did it fairly successfully. We ended up developing 2.1 Tcf of natural gas. During that process, a lot of our partners became discouraged in the downturn so we ended up buying out all of our partners and ended up with 130,000 net acres in the play and pretty much controlled it. That eventually is what led to Shell making a hostile tender offer in an attempt to buy us. We ended up selling Barrett Resources to Williams instead of Shell for $2.8 billion. So we ended up with plenty of happy shareholders.